Search

⌘K

Early Access

ML System Design in a Hurry

Generalization

Understanding model capacity, regularization, and how to assess when your ML model is over or underfitting the data.

The core goal of machine learning is generalization: training a model that performs well on new, unseen data. While there are domains of machine learning where generalization is less important, for almost all industrial applications this is the primary goal. But generalization is far harder than it sounds, and practicing ML engineers will spend a large portion of their time trying to achieve it.

The stakes are high in production systems. Models that fail to generalize either bomb immediately in production or degrade quickly over time. Both waste compute, engineering time, and user trust.

In this core concept we're going to cover some of the key failure modes of generalization and how to address them: monitoring and correcting for data drift, balancing model capacity with data, using regularization to improve generalization, and assessing whether your model will actually work in production.

A lot of beginning engineers think of generalization as a binary problem - either you're overfitting or you're underfitting. This is an oversimplification. While there are some edge cases that are clearly broken, in many cases overfitting and underfitting are part of a large gray area of underperformance. In reality, you can be overfitting some data and underfitting other data at the same time. And while some failures are easy to spot (by looking at training and validation loss curves), many real problems like data leakage or drift are substantially harder to diagnose, which makes this a rich area for interviewers to probe to assess your real-world experience.

Overfitting and Underfitting

Let's start with the basics. Overfitting and underfitting are two terms which are used to describe the two ends of the generalization spectrum. Our models effectively become a "theory" for how the inputs relate to the outputs. Good theories, per Einstein, are "as simple as possible, but no simpler".

Overfitting happens when your model learns the training data too well. It memorizes noise, quirks, and outliers instead of learning the underlying patterns or structure of your data. The model performs great on training data but terribly on new data it hasn't seen before.

Think of it like a student who memorizes every practice exam word-for-word but can't answer a single question that's phrased differently. The model has high variance: small changes in training data lead to wildly different learned patterns.

Underfitting is the opposite problem. The model is too simple to capture the patterns in your data. It performs badly on both training and test data because it never learned anything useful in the first place.

This is like a lazy student who skims past examples and learned the professor tends to answer yes/no questions in the negative. They haven't learned much and aren't going to do well on the exam. The model has high bias: it makes strong, wrong assumptions about the data that prevent it from learning.

In interviews, candidates often say "we need to avoid overfitting" without explaining what that actually means or how they'd detect it. Be specific. Talk about training vs validation performance, and have a plan for what you'd measure.

Spotting the Difference

The classic diagnostic for assessing overfitting and underfitting is to hold out a portion of the data we use to train our model for validation. We then train our model on the training data and evaluate its performance on the validation data. By doing so, the model never has a chance to "cheat" by memorizing the validation data.

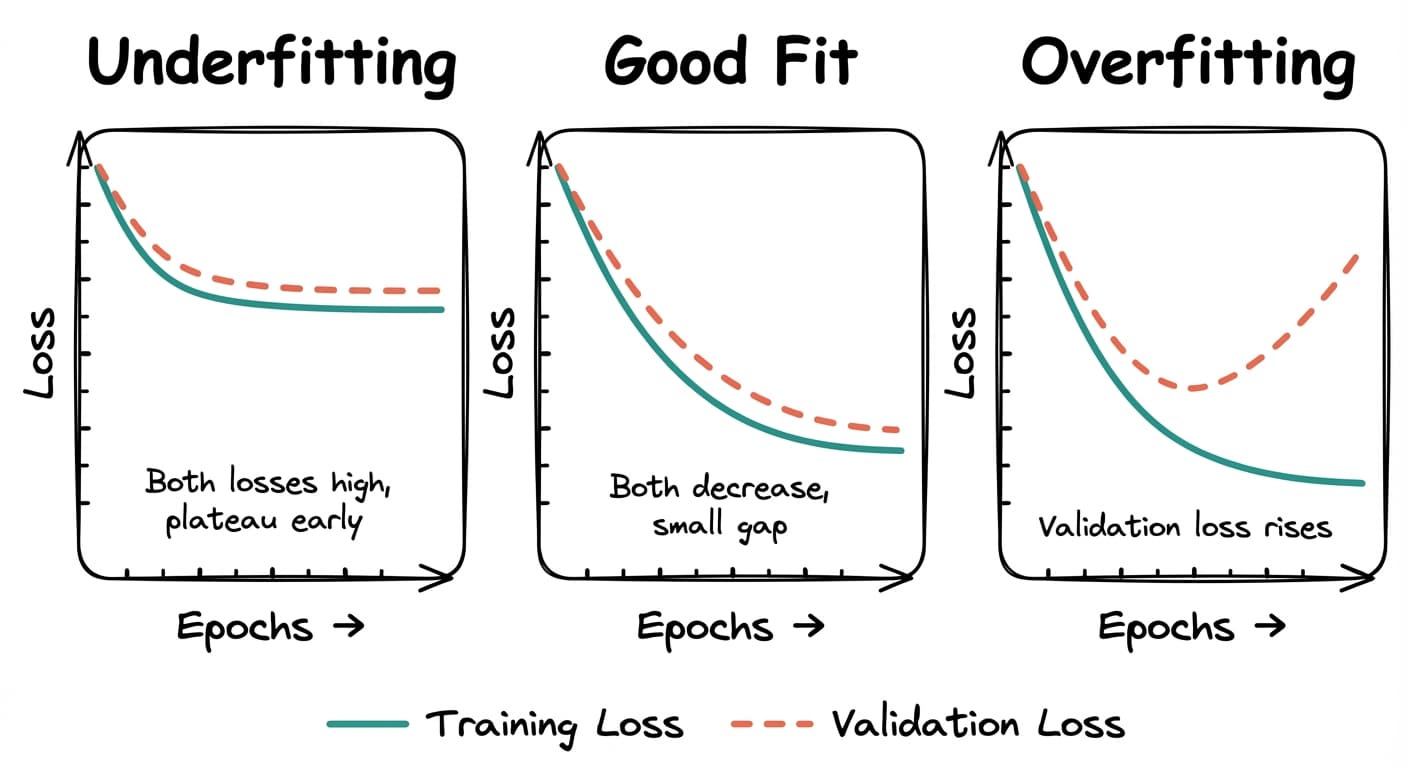

After training, we plot training loss and validation loss over epochs during training. Overfitting is easier to spot than underfitting if you're just looking at a single plot.

Loss curves showing underfitting, good fit, and overfitting patterns

Underfitting: Both training and validation loss are high and decreasing slowly or plateauing early. The model isn't learning much.

Good fit: Training loss decreases steadily. Validation loss decreases and stays close to training loss. The gap between them is small.

Overfitting: Training loss keeps decreasing, but validation loss stops improving or starts increasing. The model is memorizing training data instead of generalizing.

Deciding which data to hold out for validation is an art. Holding out random data can work for some scenarios, but not others.

Consider an application where we're trying to predict stock returns. If we randomly hold out stock tickers, the model will still be able to "see" market-wide trends and crashes. Even if I didn't have Disney in my training set, if I knew the rest of the market dropped by 20% in April predicting the drop for Disney would be easy even if I didn't have April for Disney! But this gives me a false impression of my model's performance when I actually try to deploy it in the real world where I don't have access to the rest of the market.

In these instances, slicing by time is often a good approach. But each problem may require slightly different treatment.

The other way to detect overfitting is your model does significantly worse in production than it did in your notebook or during training. In fact, a common question from interviewers is "let's assume you deploy this to production and it dramatically underperforms expectations, what do you do?"

Underfitting is usually a problem of picking the wrong model for the job. Interviewers are most often concerned with overfitting. But what can we do about it? Let's talk about some of the macro options before we get into the fine details of regularization.

Model Capacity and Data Requirements

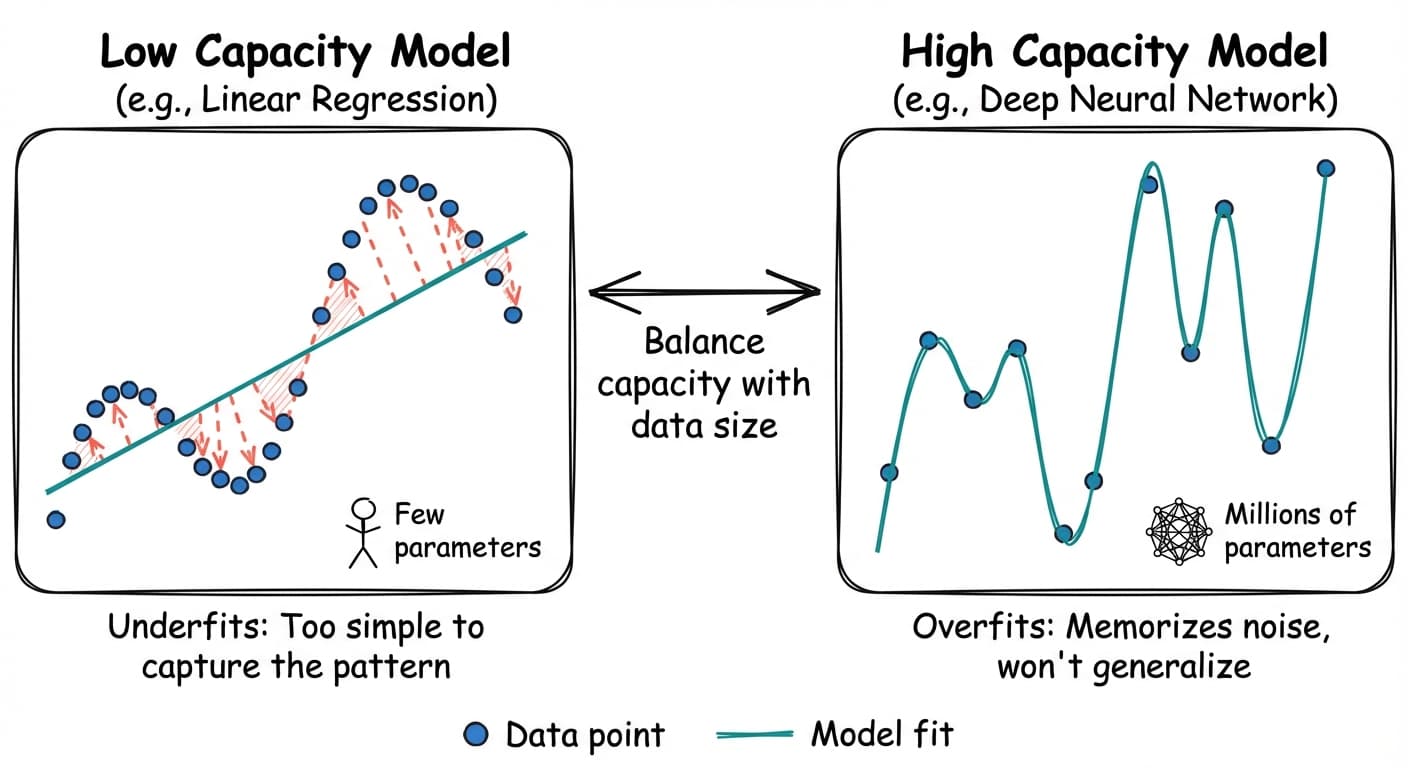

Our first stop is managing our model capacity. Model capacity is roughly how complex a function your model can represent, and typically practitioners will talk about it in terms of the number of trainable parameters in the model.

Two illustrative examples:

- A simple linear model has low capacity. It's very difficult for a linear model to learn a more complex function (even a sine wave) which means it's prone to underfitting. But on the plus side, it's almost impossible to overfit a reasonably-sized linear model.

- A deep neural network, on the other hand, has high capacity. It can learn a very complex function, but it's also prone to overfitting if you give it too little data.

Model capacity comparison: low capacity models underfit, high capacity models overfit

Remember this: high-capacity models need more data to generalize well. If you give a huge model a tiny dataset, it will overfit almost immediately. It has so much freedom that it can memorize every training example instead of learning patterns.

A very common flag in ML design interviews are candidates who try to train huge models end-to-end with very limited data. This is usually an indication you haven't trained many models and interviewers are extremely sensitive to it.

Modern deep learning models have millions or billions of parameters. GPT-3 had 175 billion parameters. A typical image classifier might have 20-50 million. Each parameter is something the model can tune during training. More parameters mean more flexibility, which means more capacity to fit complex patterns. But it also means more capacity to fit noise. So one technique to mitigate overfitting is to use a smaller model.

"We definitely don't have enough data to train a large model from scratch. I think I'd start with a baseline of a simple logistic regression. This won't learn interactions between features, but is lightning fast, won't overfit, and will give us a good baseline to compare to."

Transfer Learning and Small Data

But what if we want the power of a large model with limited data? Training from scratch would overfit almost immediately. What do you do?

Transfer learning is one of the best approaches. The idea is simple: take a model that has already learned useful features from a large dataset and fine-tune it on your smaller dataset. A model pre-trained on millions of images has already learned to detect edges, textures, shapes, and objects. You don't need to relearn all that from scratch. Instead, you freeze most of the pre-trained weights and only train the final layers on your specific task.

This works across domains. BERT has 110 million parameters, but you can fine-tune it on just a few thousand examples for text classification because it's already learned language structure from billions of words. ResNet can classify your niche product images with a few hundred examples per category because it's already learned visual features from ImageNet.

In practice, the lower layers in neural networks learn general features (edges, common word patterns) while higher layers learn task-specific features (specific objects, sentiment). By transferring the general features, you only need to learn the task-specific parts from your limited data.

Most industrial systems will do a bit of surgery. They'll extract the parameters and layers from a pre-trained base model, freeze them during training (to avoid overfitting!), then add trainable layers on top for their specific tasks. This might be a new classification head, a LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) adapter, or an entirely different architecture.

"I'll take a pretrained model and freeze some of the initial layers. Then we can train it with our more limited data to fine-tune it for our specific task."

Data Augmentation, Self- and Semi-Supervised Learning

Two other techniques complement transfer learning when battling overfitting.

Data augmentation generates synthetic training examples by transforming your existing data (rotations, crops, paraphrasing) to expose the model to more variety. This is very common for computer vision models, but a bit trickier for NLP and other domains. Data augmentation works best when you have a good understanding of corruptions that can happen in your data.

While data augmentation can be very powerful in places, it's not a silver bullet. In many instances, generating diverse, high-signal synthetic examples can be harder than the original problem (e.g. of separating cats from dogs). Typically data augmentation is used to solve a particular problem (e.g. adding noise, rotations) rather than as a general solution to data scarcity.

If you're planning to use an LLM to generate data for your problem, a useful question to ask is "why not just use the LLM to generate the labels directly?" There are valid situations, but it's good to have the discussion to show you understand.

Self-supervised learning uses your large pool of unlabeled data to learn useful representations first, then fine-tunes on labeled examples. The model creates its own supervision signal from the data itself—predicting masked words, reconstructing corrupted images, or predicting the next frame in a video. Similar to transfer learning, but instead of starting from a pre-trained model, you start from scratch and use the unlabelled data to guide your training.

Semi-supervised learning takes a different approach: it uses a small amount of labeled data alongside a large pool of unlabeled data during training. Techniques like pseudo-labeling or consistency regularization let the model learn from both simultaneously. This works well when labeling is expensive but unlabeled data is plentiful.

In interviews, show you understand that small-data problems are common in production - new products, niche domains, and cold-start scenarios don't come with millions of labeled examples. Knowing when to reach for transfer learning versus when a simpler model is the right call is essential.

Data Drift

So far we've been operating with the assumption that the data we're using to train our model is generated by the same process that will generate the data we're using in production. But this is rarely the case in real systems.

Data drift is when the distribution of your production data changes over time compared to your training data. Your model learned patterns from historical data, but the real world changed, and those patterns don't hold anymore.

This is different from overfitting. You might have a perfectly well-generalized model that performed great when you deployed it, but six months later it's failing because the data itself changed.

Types of Data Drift

Data drift can appear in different ways, but the story is the same: the training data is no longer a good representation of the production data.

Covariate shift happens when the distribution of your input features changes, but the relationship between features and labels stays the same. For example, a recommendation system trained on summer user behavior sees different patterns in winter. The features (time of day, categories browsed) have different distributions, but if you'd trained on winter data with the right labels, the model would still work.

Prior probability shift (or label drift) happens when the distribution of your target variable changes. Maybe you built a fraud detection model when fraud was 1% of transactions, but now it's 3%. The model's decision threshold might not be calibrated correctly anymore.

Concept drift is the nastiest type. The actual relationship between features and labels changes. User preferences evolve, competitor products launch, regulations change, or world events alter behavior. The patterns your model learned are just wrong now.

Depending on the problem, it's common for interviewers to ask about how to deal with this hairy issue. You'll want two pieces: detection and remediation.

Detecting Data Drift

First, to detect data drift, there's a number of weapons in your arsenal. Mature production systems will use many of these:

Monitor prediction distributions: Track the distribution of your model's predictions over time. If your fraud model suddenly starts flagging 10x more transactions, something changed. Either fraud patterns shifted, or your input data distribution changed.

Monitor feature distributions: Track statistics on your input features. Calculate mean, variance, percentiles for numerical features. Track category frequencies for categorical features. Set up alerts when these drift beyond acceptable thresholds.

Monitor performance metrics: Track your model's actual performance on labeled production data. If accuracy, precision, or recall degrade over time, you've got drift. The challenge is getting ground truth labels quickly enough to catch drift before it does serious damage.

Model retraining cadence: If you're retraining regularly (weekly, monthly), compare performance on the same hold-out test set over time. Degrading performance on a fixed test set signals drift.

Data drift detection is hard and some teams try to aggressively remediate rather than detect it. Being able to talk about how you'd monitor is a useful way to show your understanding of the problem.

Handling Data Drift

Once you've detected drift, what do you do?

The biggest thing is to retrain regularly. This, of course, is less common than you might assume in real teams partly because production pipelines are hard to get right. But retraining regularly ensures that your model has fresh, near-current data to learn from, minimizing the risk of drift. In an interview setting, it's free to suggest that you'll do the thing that people should be doing anyways, so start here.

"I expect this domain to drift considerably over time. I'm going to have automated retraining once a week to balance operational concerns with the performance degradation I'd expect from drift."

Next, we need to consider approaches that carry tradeoffs.

Online learning is best for systems that need to very rapidly adapt to data drift. Some models, like logistic regression, can update continuously on new data as it arrives, but this is harder with deep learning. The risk is catastrophic forgetting: the model forgets old patterns while learning new ones. So you'll more typically see online learning when systems need to very quickly adapt to data drift. Fraud is a classic example of this.

A modern in-between approach is online embedding learning. In this approach we keep model weights frozen but have embeddings or parameters which are updated continuously. This is a prodigious engineering challenge, but required for the rapid adaptation that makes recommendation systems behind Tiktok and Instagram reels work (more on this in our Video Recommendations problem breakdown).

Less commonly used, but still valid are ensemble approaches. We keep multiple models trained on data from different time periods and weight their predictions based on which time period best matches current data. This hedges against drift but increases serving costs. Typically you'll have an ensemble for other reasons and some sort of multi-armed bandit or tournament to choose which model to use for new predictions.

Finally, for high-stakes applications, we can route uncertain predictions to humans for review with human-in-the-loop. Their feedback provides fresh training data that reflects current patterns.

If data drift is a concern for the problem you're solving, start with basic hygiene around retraining regularly and getting fresh labelled data. If there's still concerns, online learning approaches may be a good fit.

Regularization

We've talked about approaches to battle overfitting and data drift at the macro level, but what if we could force our models to learn more robust patterns in the first place? This is where regularization comes in.

Regularization improves generalization by constraining the model during training so it's more difficult to memorize noise. You're trading some training performance for better generalization on unseen data.

This helps both with overfitting during initial training and with building models that degrade more gracefully when drift happens. A well-regularized model that learned robust patterns tends to handle distribution shift better than one that memorized brittle correlations.

Dropout and Layer Normalization

Dropout randomly disables neurons during training. On each training step, every neuron has a probability p (like 0.5) of being turned off. This forces the network to learn redundant representations because it can't rely on any single neuron always being there.

At test time, all neurons are active but their outputs are scaled down by (1-p) to account for the fact that more neurons are firing than during training. Most frameworks use "inverted dropout" instead, which scales up surviving neurons by 1/(1-p) during training so no adjustment is needed at inference.

Layer normalization normalizes activations across features within each training example. It stabilizes training and has a mild regularization effect.

If you're proposing deep models, you're talking about dropout and layer normalization. Dropout is extremely effective for preventing overfitting in large networks.

You'll still see batch normalization (batchnorm) in older architectures and CNNs, but layer normalization has largely replaced it in transformers and modern architectures. Batchnorm normalizes across the batch dimension, which creates issues with small batch sizes and makes it awkward for sequence models where different positions shouldn't share statistics. Layer normalization avoids these problems by normalizing within each example independently.

L2 Regularization (Ridge / Weight Decay)

L2 regularization adds a penalty to the loss function proportional to the square of the weights. Large weights get penalized more than small ones.

This makes weights stay smaller and more evenly distributed. The model can't rely too heavily on any single feature, which prevents it from fitting noise.

When to use it: Almost always. L2 is the default regularization technique for most models. It's cheap, effective, and doesn't complicate training much.

In practice, you tune the regularization strength (often called lambda or alpha) on a validation set. Too much regularization and you underfit. Too little and you overfit.

In interviews, L2 regularization is the first regularization technique you should mention. It's simple, well-understood, and works across almost every model type.

L1 Regularization (Lasso)

Another approach is L1 regularization. This adds a penalty proportional to the absolute value of the weights. Unlike L2, L1 pushes weights all the way to zero, effectively performing feature selection.

The effect: sparse models where many weights are exactly zero. Only the most important features survive.

When to use it: When you have many features and suspect most aren't useful. L1 gives you interpretability by showing which features matter. It's common in linear models and logistic regression, less common in deep learning. L1 regularization can be really helpful in performance constrained scenarios: you can prune features (or sometimes weights) to get a simpler model that still performs well.

Early Stopping

Before, we noted that the graphs of overfit models tended to get better then start to perform worse as the model continues to train. We can exploit this. Early stopping is simple: stop training when validation performance stops improving. You monitor validation loss during training, and if it doesn't improve for N epochs, you halt and use the model from the best epoch.

This prevents the model from continuing to overfit after it's already learned the useful patterns.

When to use it: Always. Early stopping is free and effective. It's not a replacement for other regularization techniques, but it's a good safety net.

Summary

Generalization is what separates models that work in production from expensive science projects. The main failure modes are overfitting (memorizing training data), underfitting (being too simple to learn useful patterns), and data drift (the world changing after you deployed).

You spot overfitting and underfitting by comparing training and validation loss curves. High-capacity models need more training data or they'll overfit. Transfer learning and data augmentation help when you don't have enough data.

Data drift happens when production data distributions change over time. Monitor your feature distributions, prediction distributions, and performance metrics to catch drift early. When you detect it, retrain on recent data or use online learning to adapt.

Regularization techniques like L2, dropout, and early stopping constrain your model during training so it learns robust patterns instead of memorizing noise. They're your first defense against overfitting and help build models that degrade gracefully when drift happens.

In interviews, talk about generalization whenever you're picking a model architecture, estimating data requirements, or designing evaluation strategies. Interviewers will often probe to ask about specific techniques for particular challenges of a given problem. Be specific about techniques and explain how you'd measure it. Connect everything back to building a model that actually works for real users in production. The key is to send the impression to your interviewer that you've worked to optimize real models in production, not just read the papers.

Mark as read

Track your interview readiness

Your personal checklist helps you know what to study and keep track of your progress.

View ChecklistReading Progress

On This Page

Overfitting and Underfitting

Spotting the Difference

Model Capacity and Data Requirements

Transfer Learning and Small Data

Data Augmentation, Self- and Semi-Supervised Learning

Data Drift

Types of Data Drift

Detecting Data Drift

Handling Data Drift

Regularization

Dropout and Layer Normalization

L2 Regularization (Ridge / Weight Decay)

L1 Regularization (Lasso)

Early Stopping

Summary

Schedule a mock interview

Meet with a FAANG senior+ engineer or manager and learn exactly what it takes to get the job.

Your account is free and you can post anonymously if you choose.